Untitled (Denis with Waves), 81” x 41” oil and copper leaf on canvas, October 2025

Girl in Green Dress, 12” x 9”, graphite and watercolor on paper, July 2025

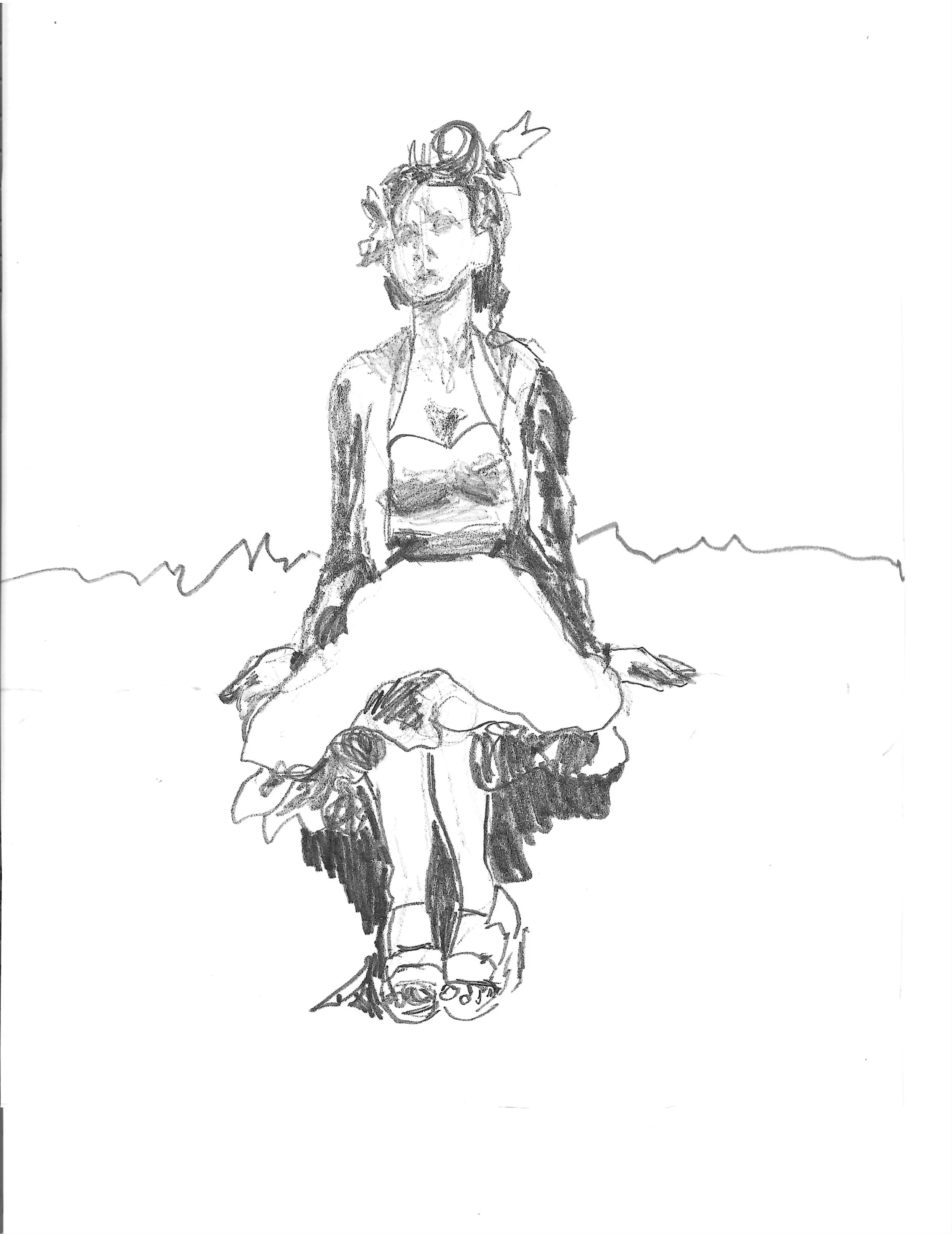

Girl in Blue Dress, 12” x 9”, graphite and watercolor on paper, July 2025

Untitled, 24” x 24”, oil on canvas, June 2025

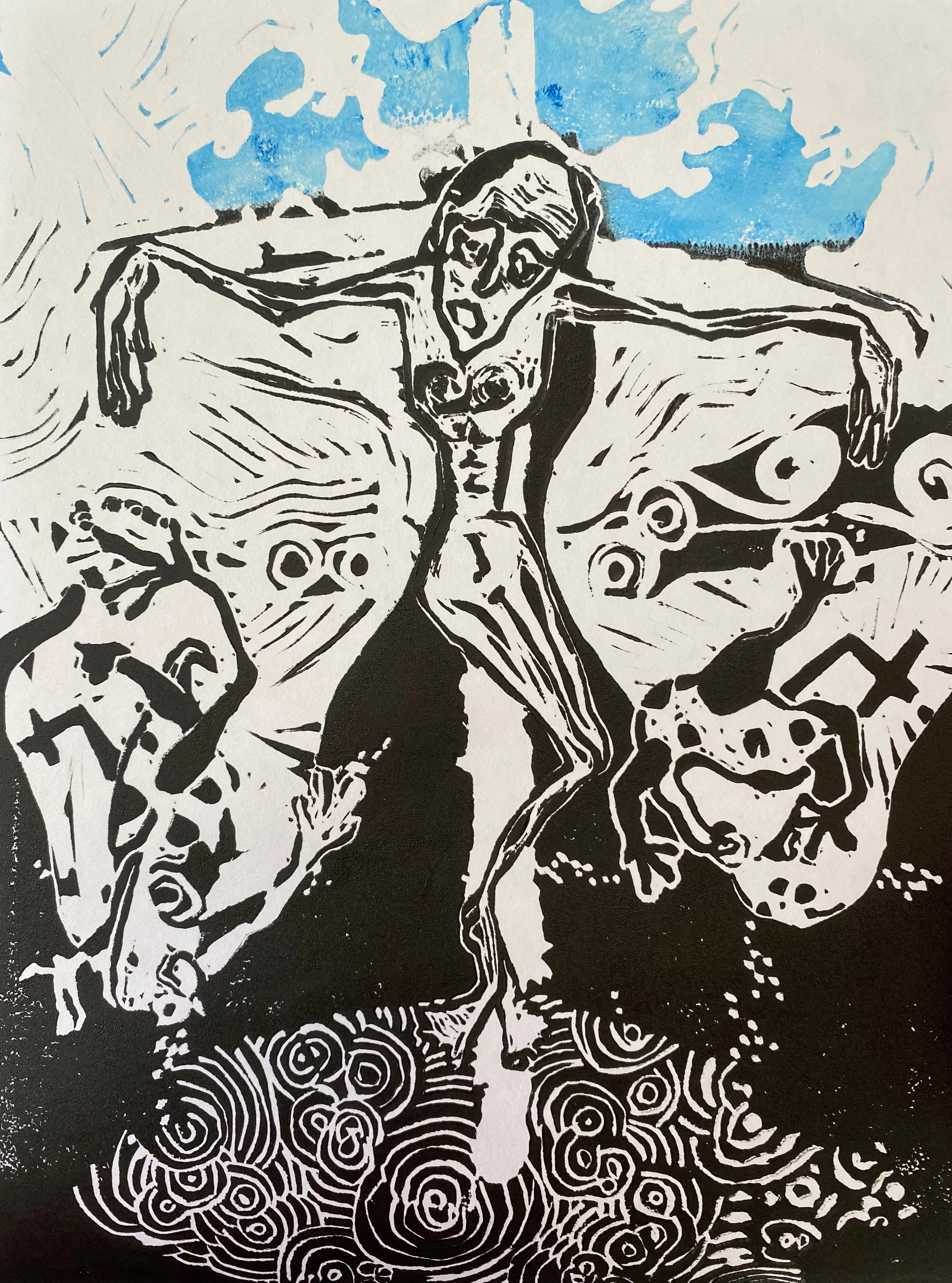

Jesus with Criminals, 12” x 9”, ink block print on paper, September 2025

Bride with Padrinos, 12” x 9”, watercolor on paper, August 2025

I Just Met a Girl Named Maria, 9” x 12”, watercolor and posca marker on paper, August 2025

Max from Pennsylvania, 12” x 9”, watercolor and posca marker on paper, August 2025

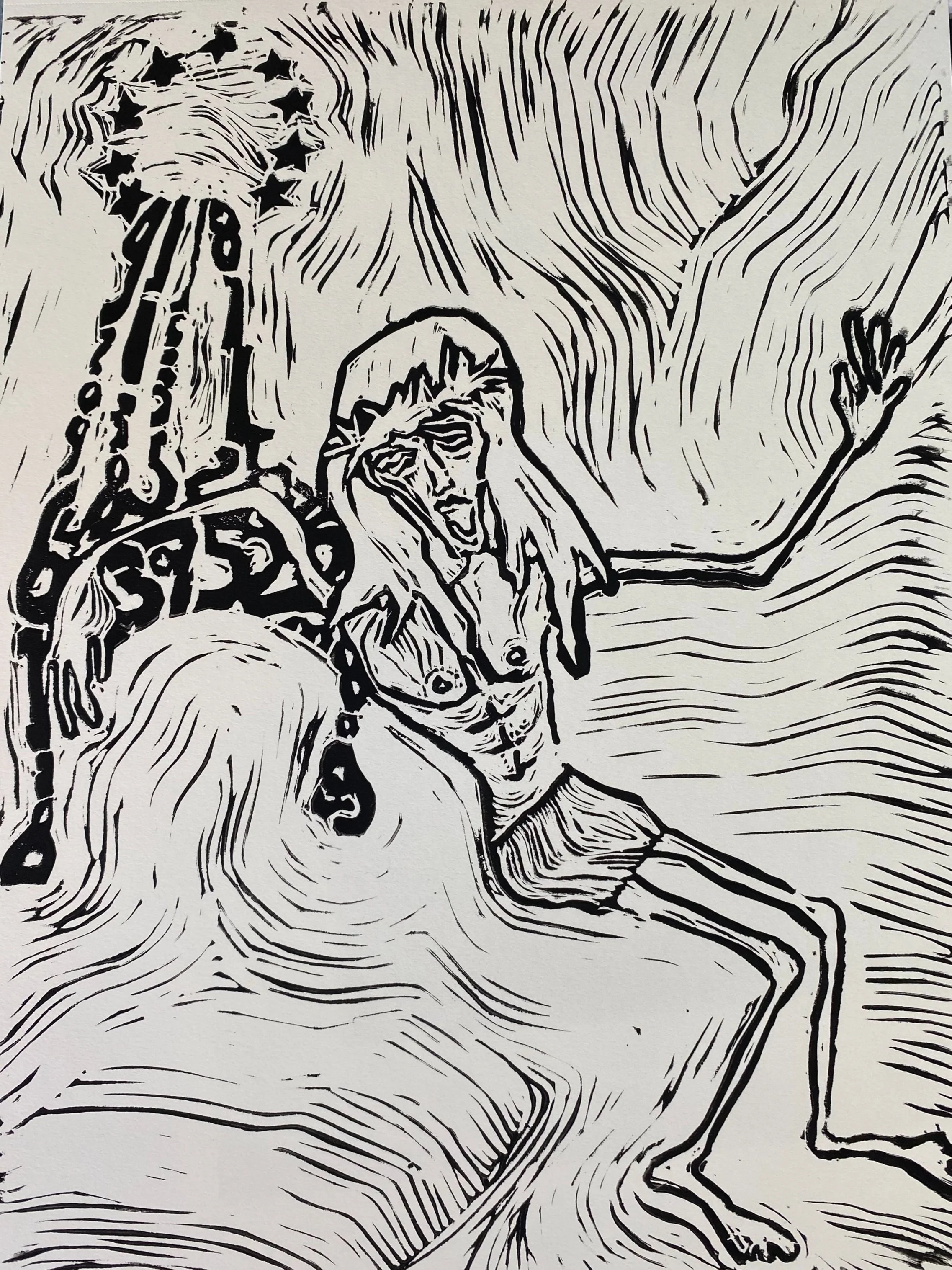

Jesus with Throne of Numbers, 12” x 9”, ink block print on paper, July 2025

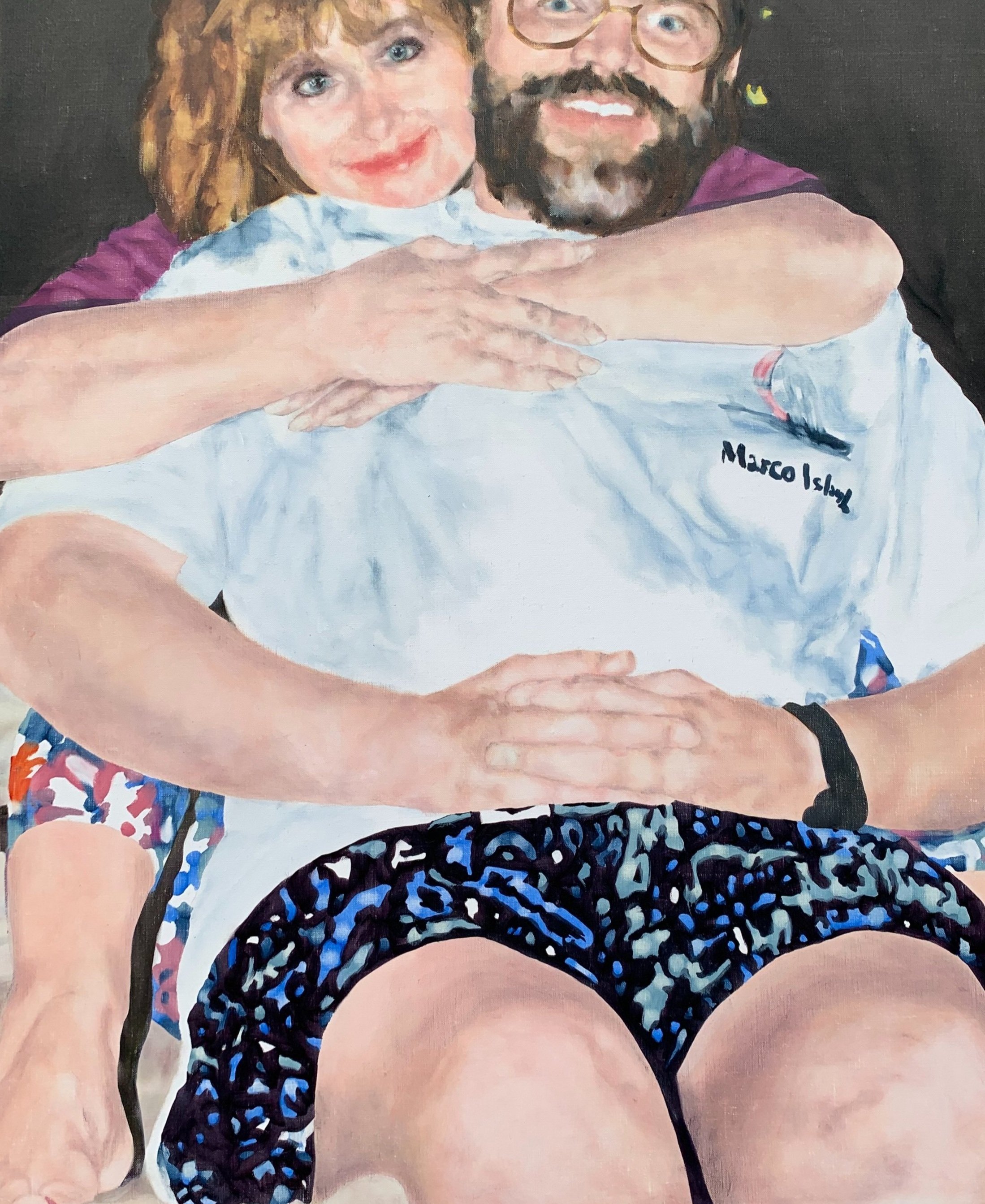

Untitled, 18” x 24”, oil on canvas, July 2025

Untitled, 18” x 24”, oil and posca marker on canvas, June 2025

Untitled (Aunt Bobby’s Tomatoes), March 2025, 9” x 12”, pen and acrylic on paper

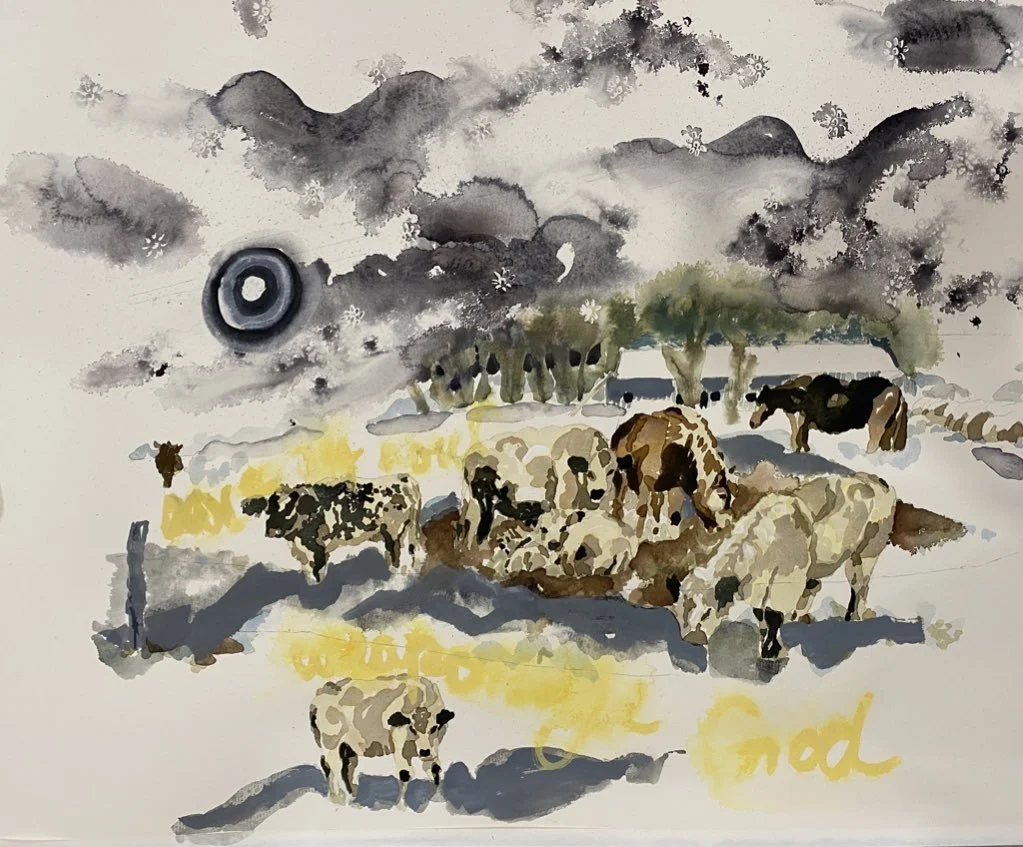

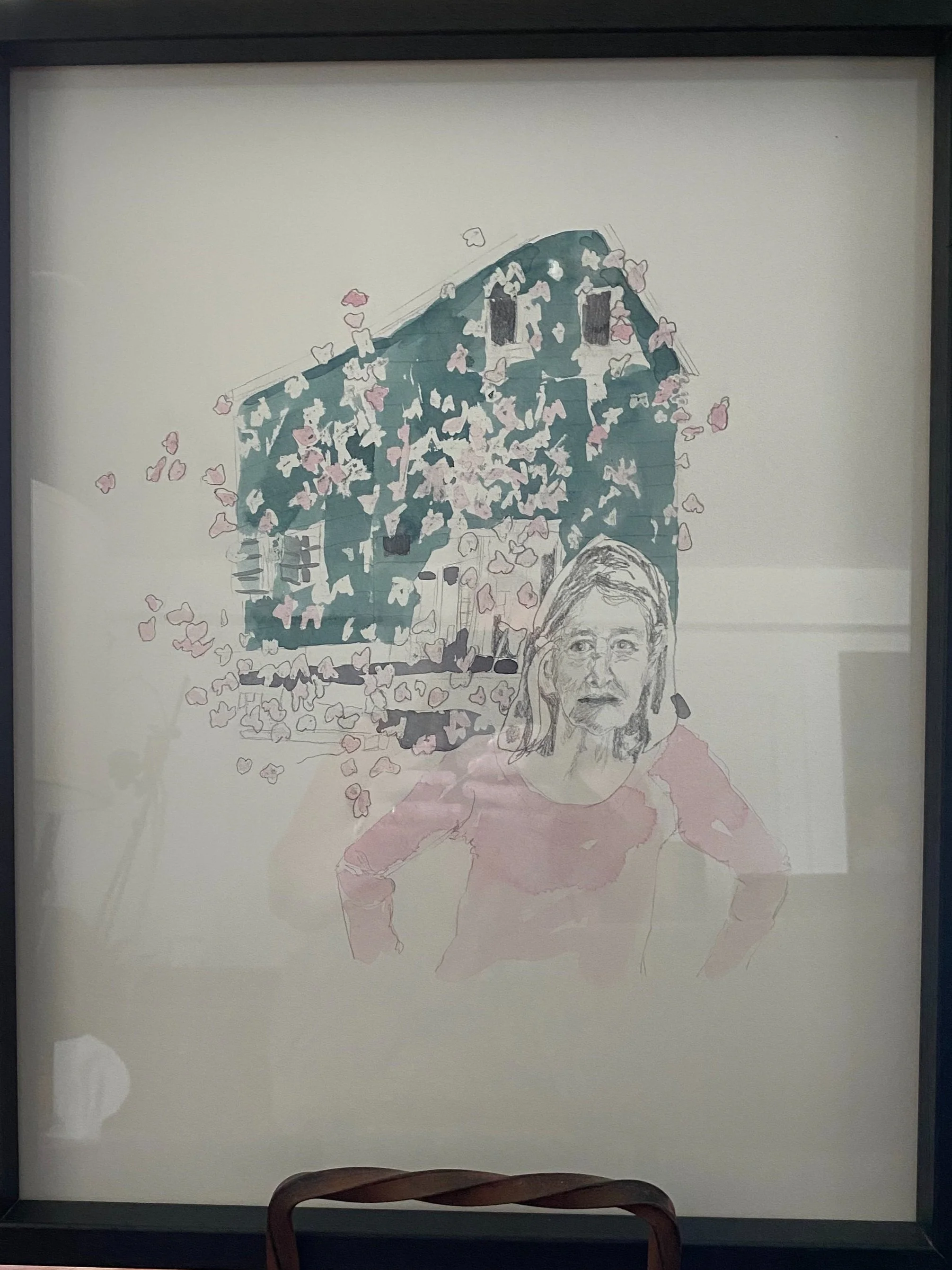

Untitled, 22” x 30”, watercolor and gouache on paper, January 2025

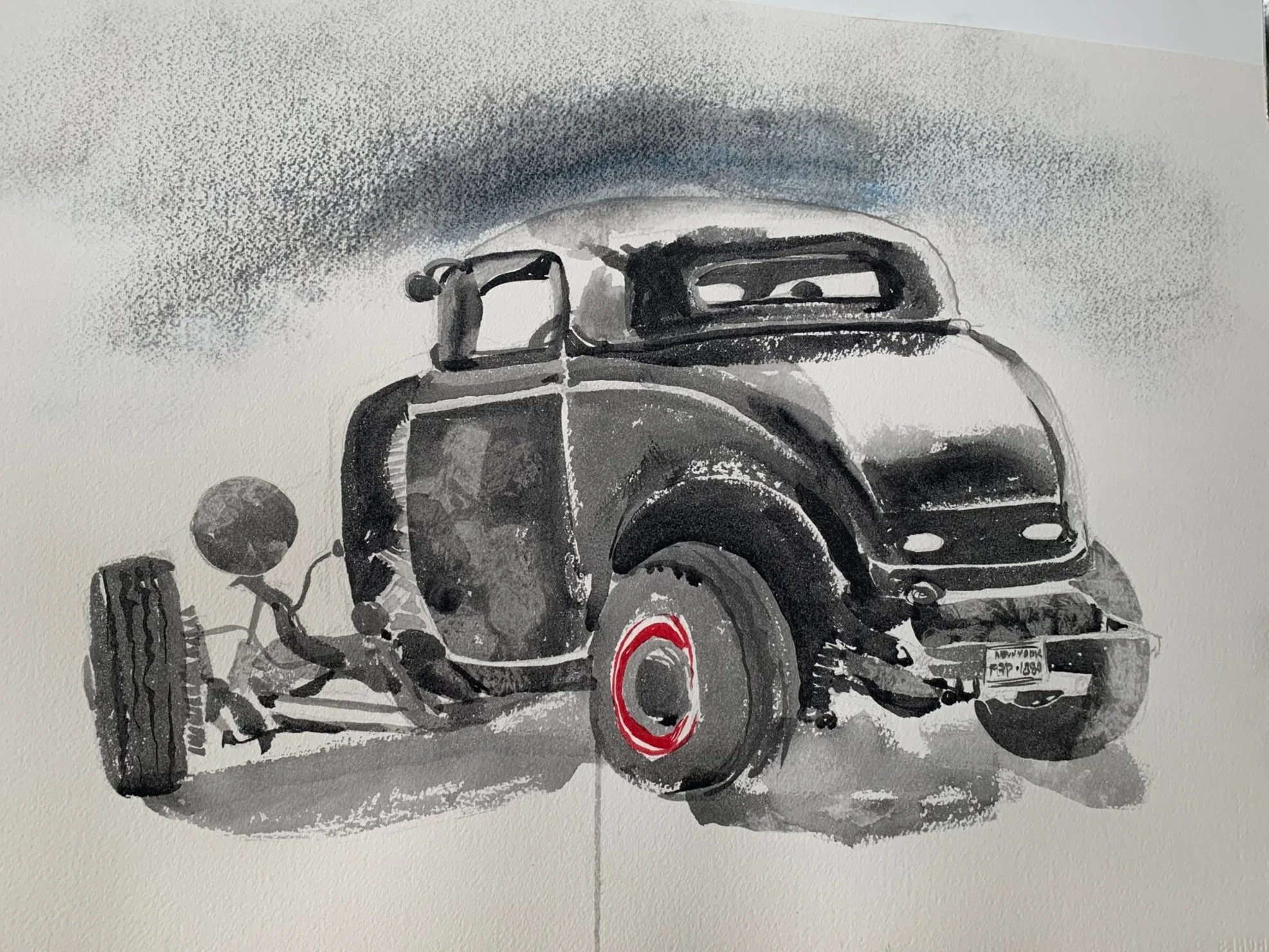

Untitled, 22” x 30”, watercolor on paper, January 2025

Untitled, 9” x 12”, watercolor on paper, April 2025

Hi Diana. This is your painting.

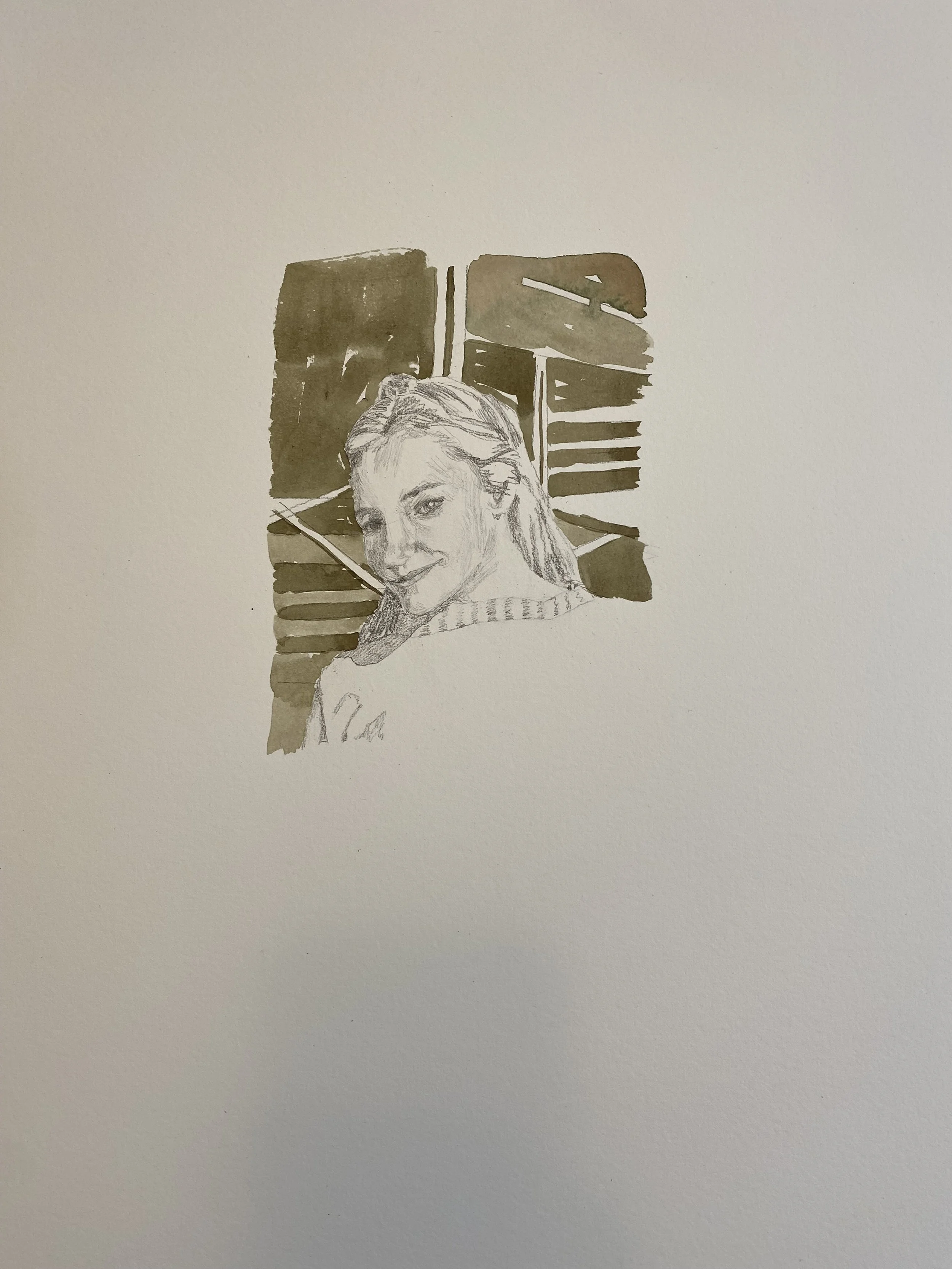

Perdido Key (Diana), 12” x 9”, watercolor on paper, February 2025

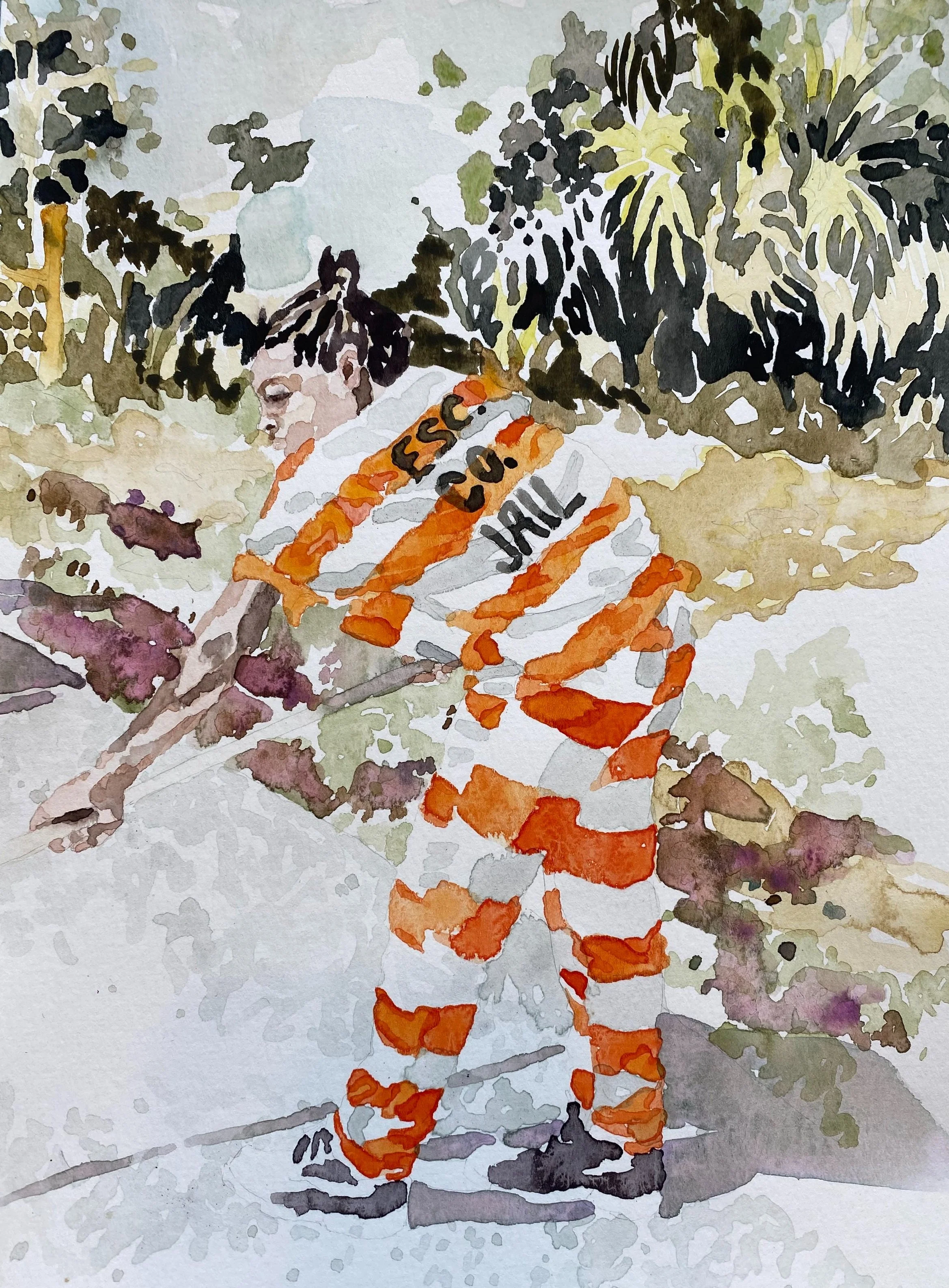

Untitled (Perdido Key-Chain Gang), 12” x 9”, watercolor on paper, February 2025

Untitled (Perdido Key-Denis Matthew), 12” x 9”, watercolor on paper, February 2025

Untitled (Perdido Key-Woman at Publix), 12” x 9 “, watercolor on paper, February 2025

Untitled (Perdido Key-Blue House), 9” x 12”, watercolor on paper, February 2025

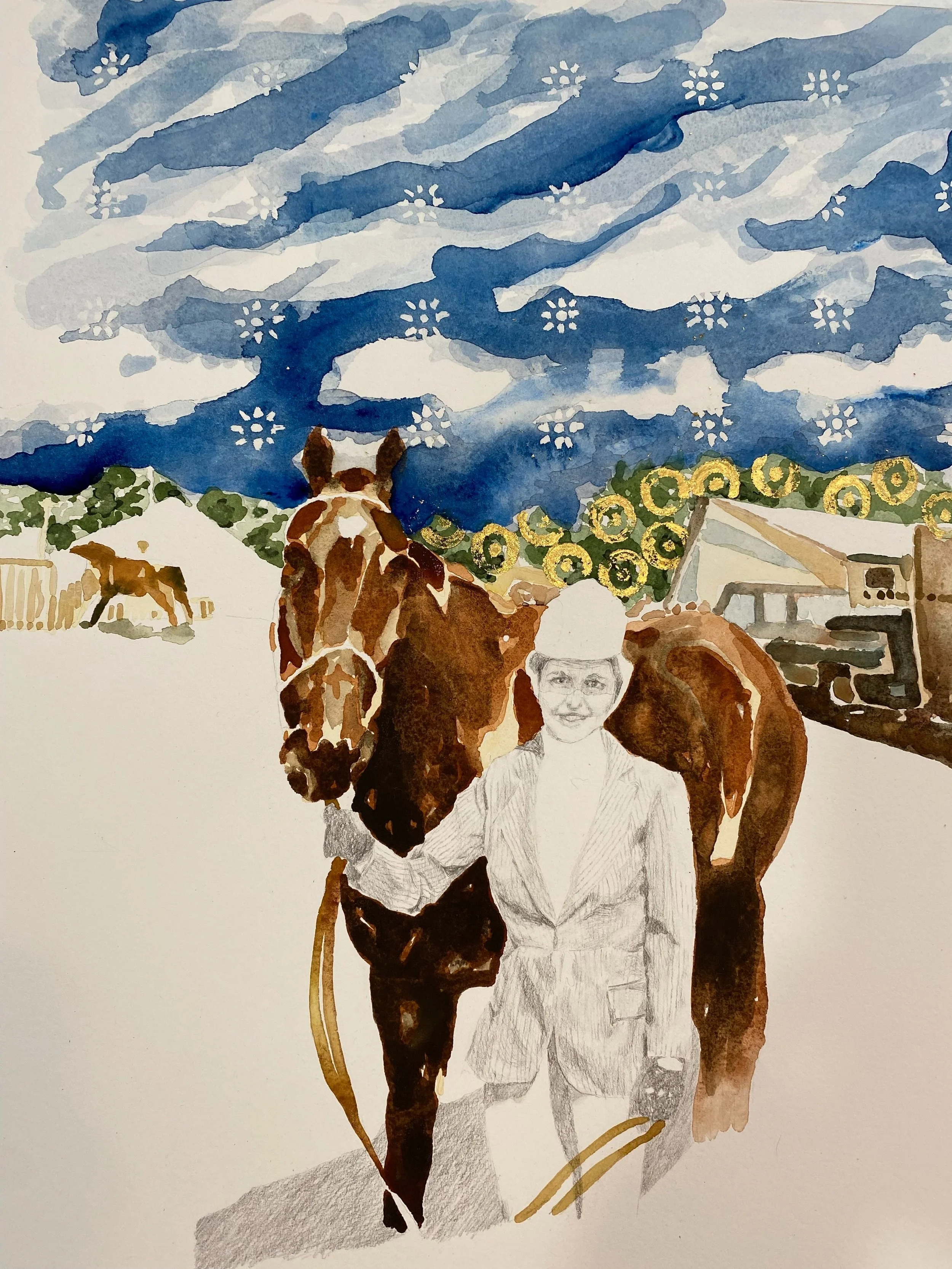

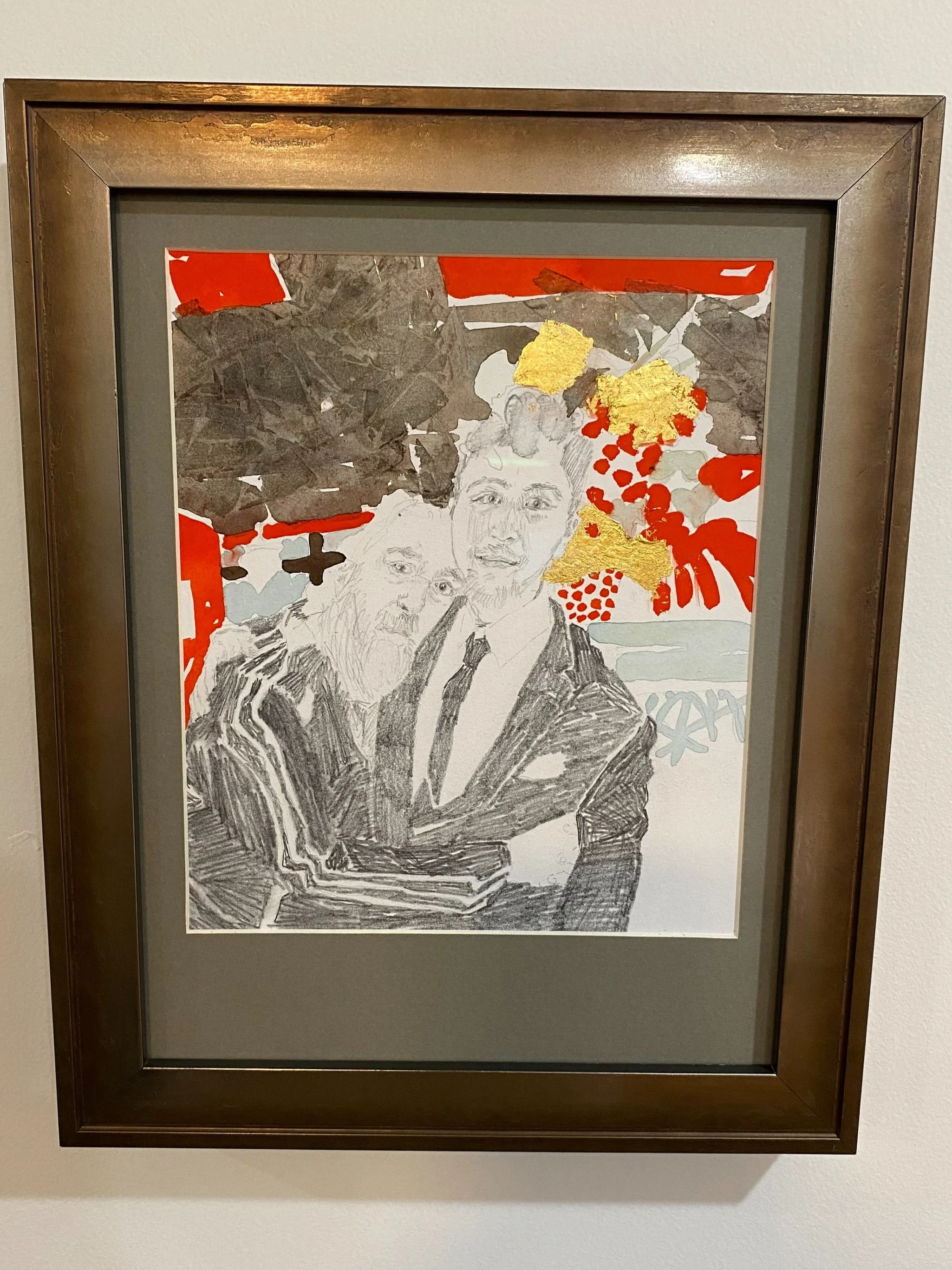

Linda and Moody Blues, Dimensions TBD, graphite, watercolor, and 24k gold leaf on paper, January 2025

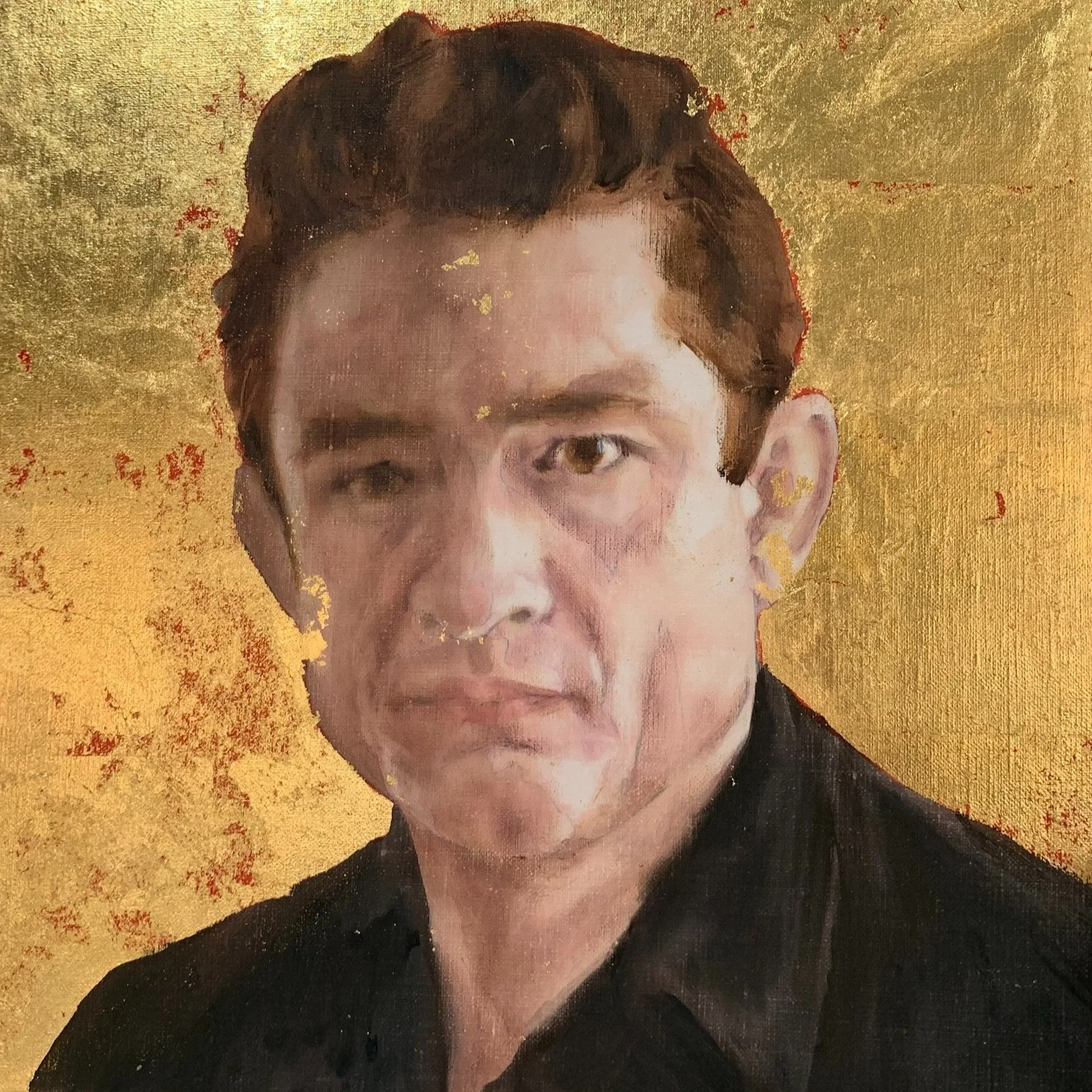

Endangered Species Series #1, Denis Arthur, 60” x 24”, oil and 24k gold leaf on canvas, December 2024

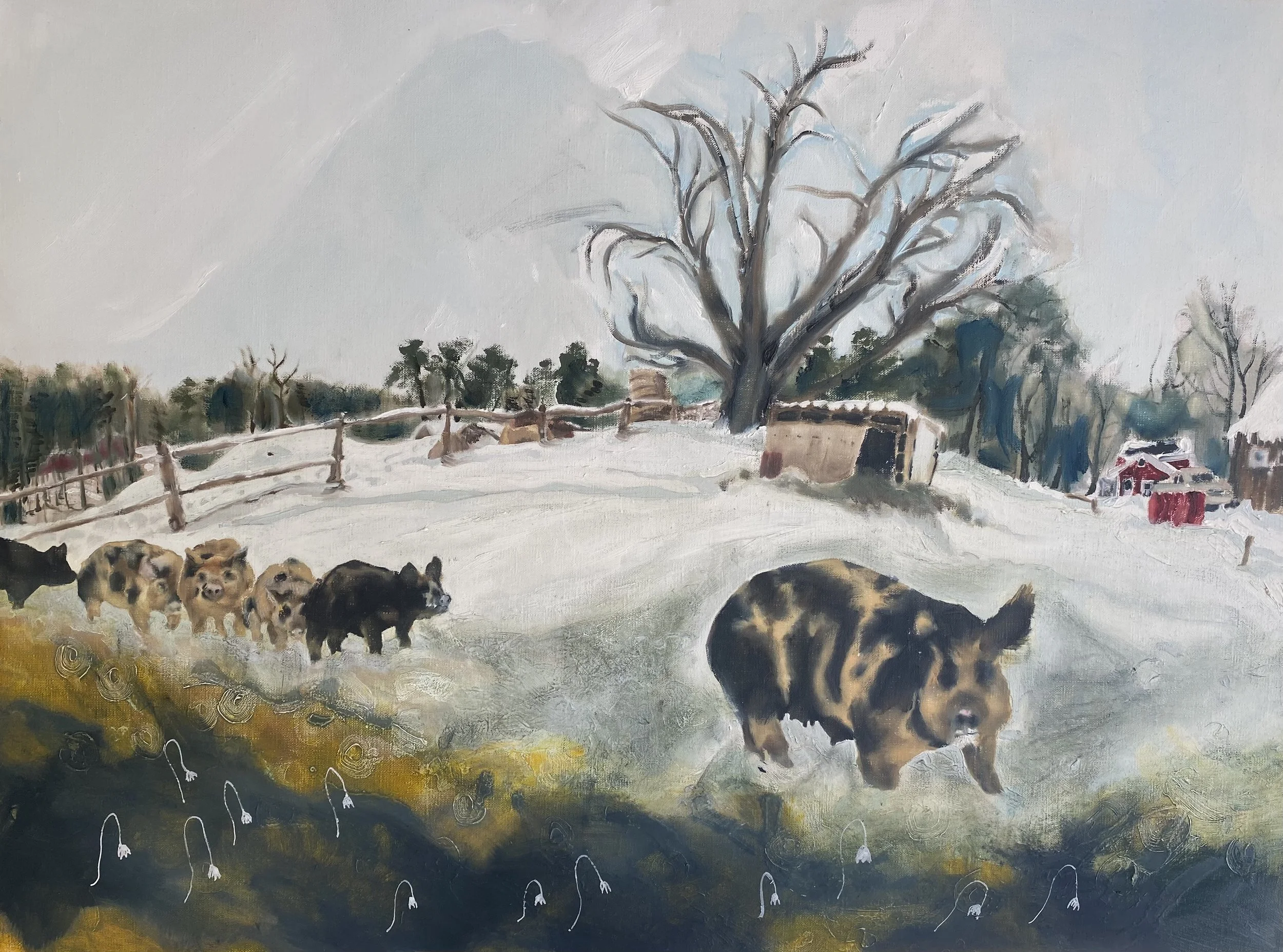

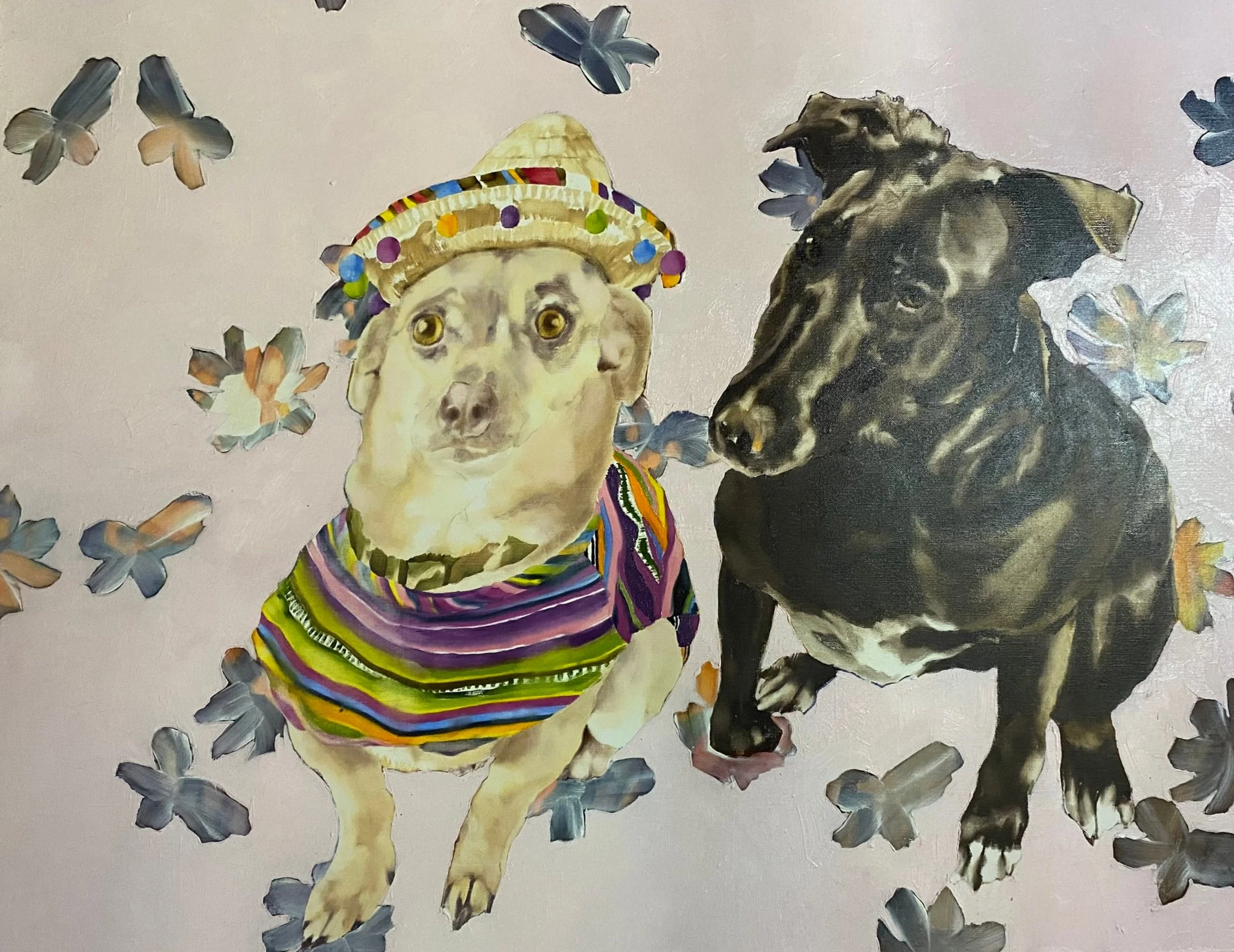

Las Vacas (The cattle were lowing.), 18” x 24”, oil on canvas, October 2024

Plein Air, Buffalo Creek (3 turtles), 11” x 14”, watercolor and acrylic on canvas, September 2024

Plein Air, Buffalo Creek, 11 1/4” x 9 1/4”, pen and watercolor on paper, September 2024

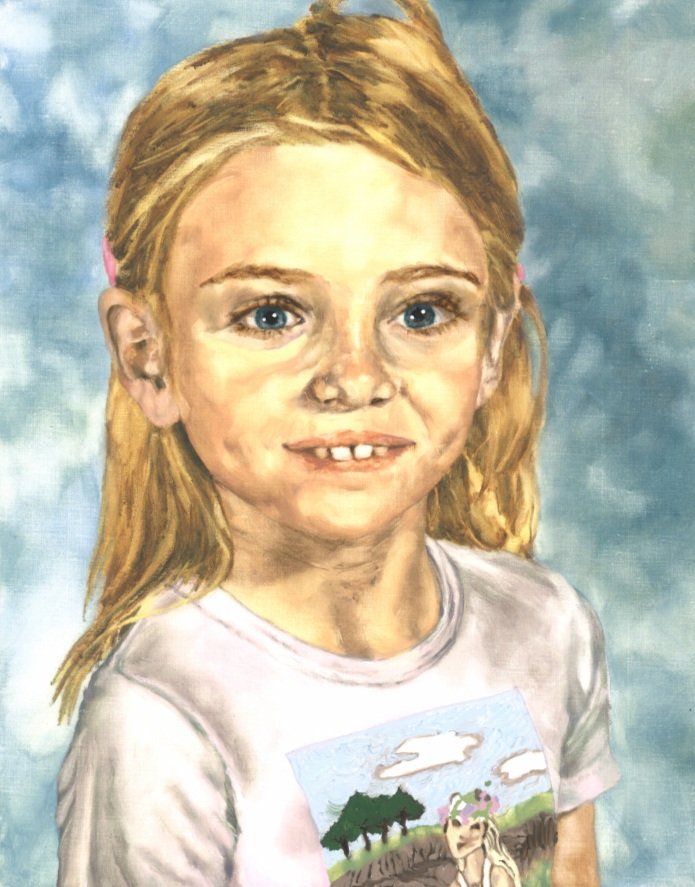

The Wisdom of Innocence,

5 ft. x 7 ft., oil on canvas, July 2024

What is unimaginable, leaving a child’s heart beating but rendering it without its intrinsic value: the ability to trust God's love.

There is no elixir for worthlessness. It gnaws at soul and breath. It imposes life’s cruelest sentence, life without union. At five, I dreamed a horrific nightmare. Fifty years later, the image, its psychological contents, and unshakable memory still reverberate through me. I begin to paint. In the dream, all of the people in the world have been decapitated and their heads put into cages: the disembodied heads were yet alive and animated and did not seem to know of their predicament. The scene was very dark and seemed to go on inside a mammoth warehouse with countless head-filled cages stacked and scattered about. I could not tell who had done this. I thought if I could only sew my mother’s head back on, then she could help me sew the rest of the world’s heads on. I then awoke.

I was four and gangly. Holding a phone book, I was forty pounds. I remember being ugly. I was asleep. There was a bench under my aunt’s window sill just big enough for me to lie with my knees crouched up. I can’t remember why I was there but I used to wash her dishes for a quarter so it wasn’t unusual that I was there. I remember him. He was big. He was tall and cowboy thin. He always wore a brand of jeans that never fit quite right. He also regularly wore a craggy old button down with patterning, flannel or checked. It appeared to be washed but looking at it you felt it just wasn’t clean. That was the film he had, too, like you didn’t want to know more about him than what was absolutely necessary in a simple exchange. His hair was used-to-be brown but wasn’t ready to resign itself to silver yet. It was oily, parted and combed over aggressively to one side, parted very close to his ear. My zipper moved. I was so little. His belly was filled with such uneasiness. I could feel the sickness wash over me. I kept my eyes closed. I didn’t want him to see me. I pretended that I was still sleeping but that his intrusion was stirring me. He left. I can’t remember walking home. Actually, I don’t think I ever left. I mean the who who I was still exists on that dirt road in Shantytown in that ramshackle house which has since been torn down and covered over with grass and weed alike: it’s as though that place is the hologram that everywhere surrounds me through which I see the world.

As I work through the painting’s images, a second memory comes to mind and seems to be fusing with the one I just shared. Around the same age, I remember not having use of my legs. I crawled home on my belly all the way down the dirt/gravelly road crying. My mom thought that I was having some sort of bout with hypoglycemia but also remember her telling me not to go to my aunt’s house anymore. In the painting, I paint conch shells. If you put a conch shell up to your ear, you can hear the sea’s waves swelling then crashing onto the shore. BBC Science Focus contends that the sound in a conch shell is not the sound of the ocean but rather air vibrating at different frequencies-frequencies which depend on the size of the shell (www.sciencefocus.com). I, however, do believe that the sea has a memory, the conch, its recorder.

As I paint, something has happened. The sadness in the world, and the crushing disappointment of the state of things in general, has left me. It is though, there on a continuum of the present and the future, the past is irrespective of me who walks upright now.

Pretty Girl in Zebra Dress, dimensions TBD around 22” x 30 “, graphite, watercolor, acrylic, and 24k gold leaf on paper, August 2024

Plein air at Cazenovia Park, Buffalo, New York (Untitled), dimensions TBD around 22” x 30”, graphite, watercolor, acrylic, and copper leaf on paper, August 2024

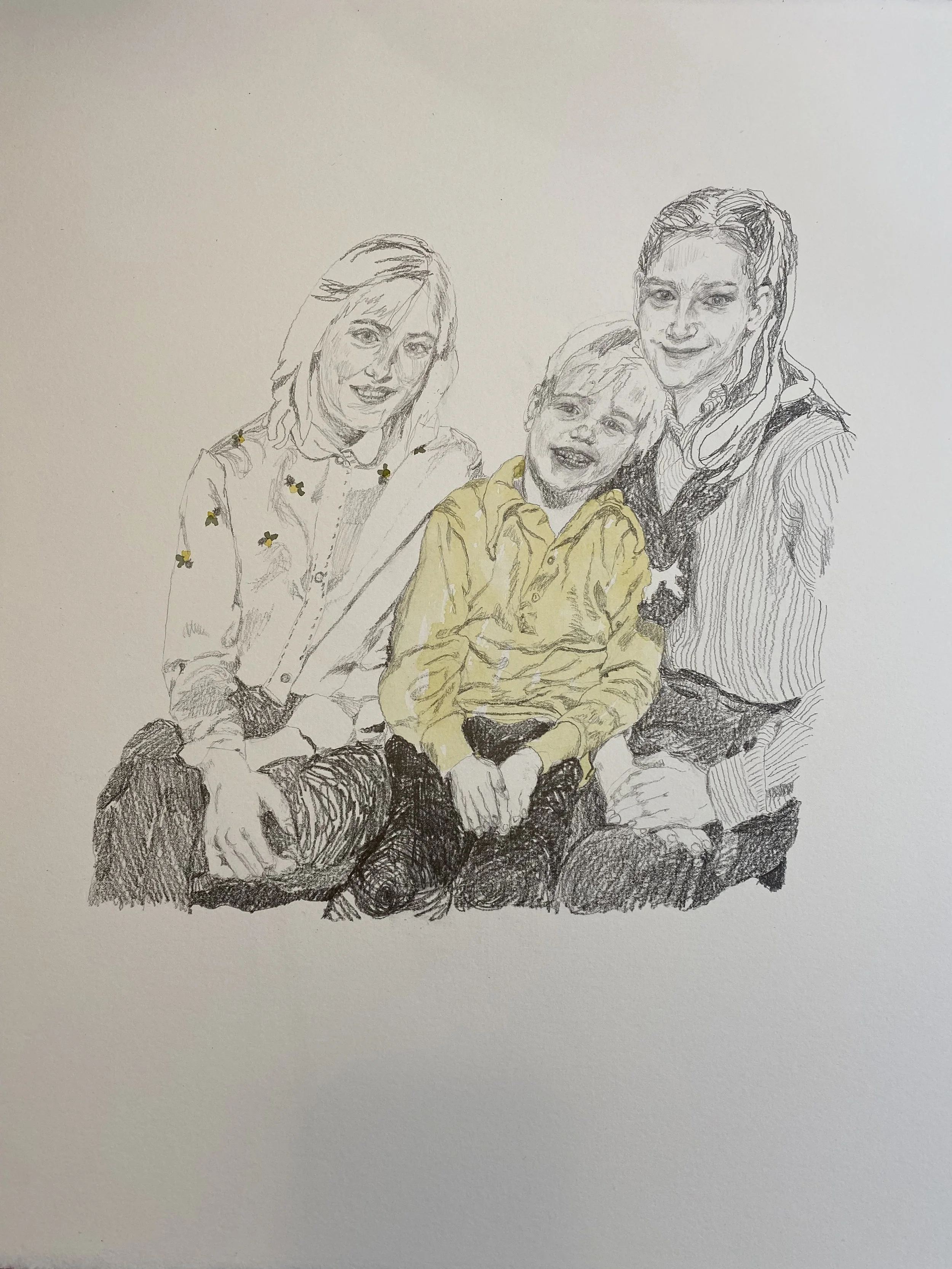

Welcoming Baby Matthew, 12 3/4” x 10 1/2”, graphite and watercolor on paper, February 2024

It’s a Terrible Life, 13 1/2” x 10 1/2”, graphite and watercolor on paper, 2023

Baptism, 12” x 12”, graphite, watercolor, and 24 k gold leaf on paper, February 2024

Answered Prayer, 11 3/4” x 14 1/2 “, graphite, watercolor, and 24 k gold leaf on paper, January 2024

Untitled, 8” x 6”, graphite and watercolor on paper, January 2024

if it be Your will, 10 3/4” x 8 3/4”, graphite and watercolor on paper, January 2024

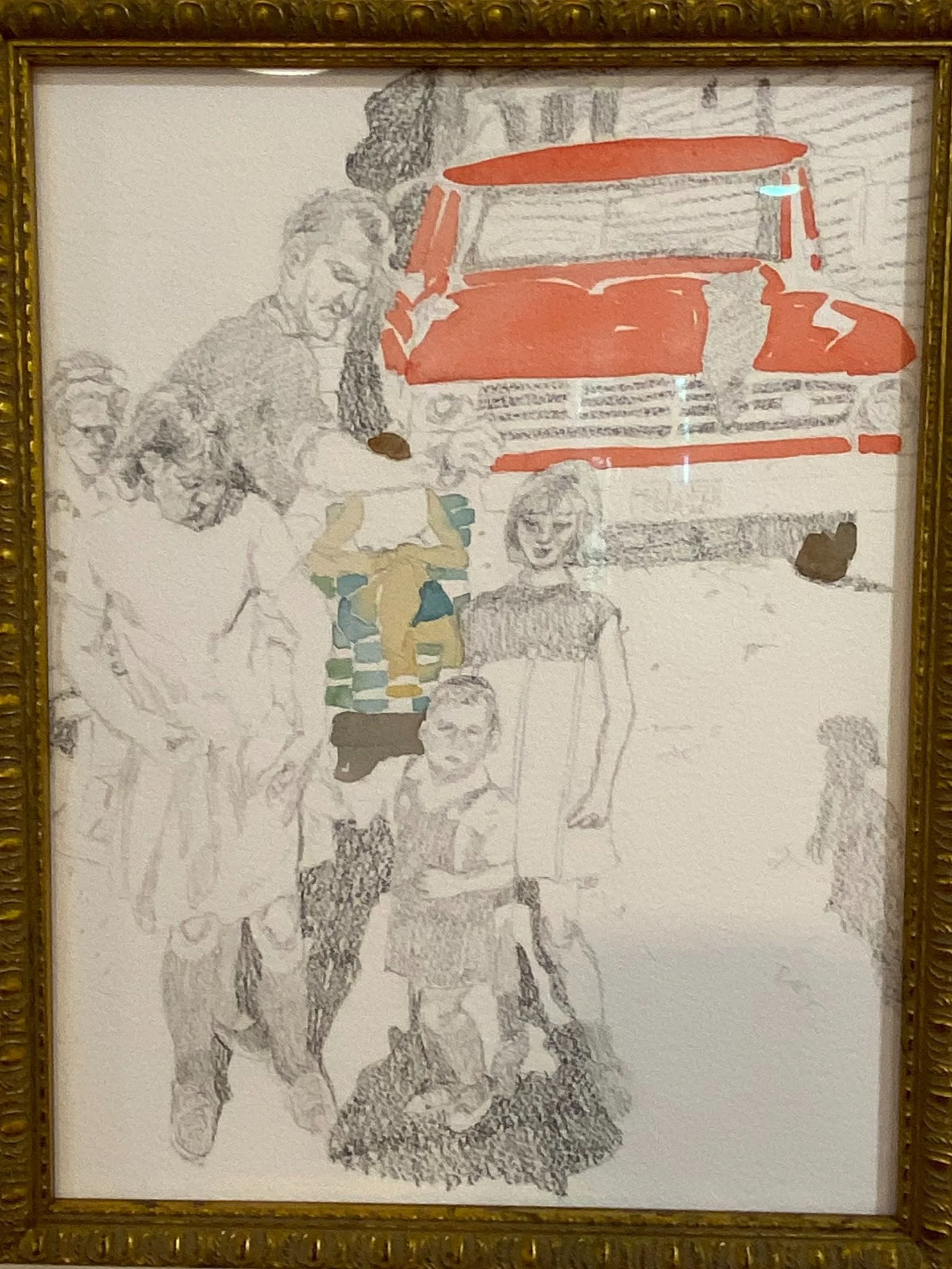

Untitled (Fourth of July), 12 1/4” x 9 3/4”, graphite and watercolor on paper, January 2024

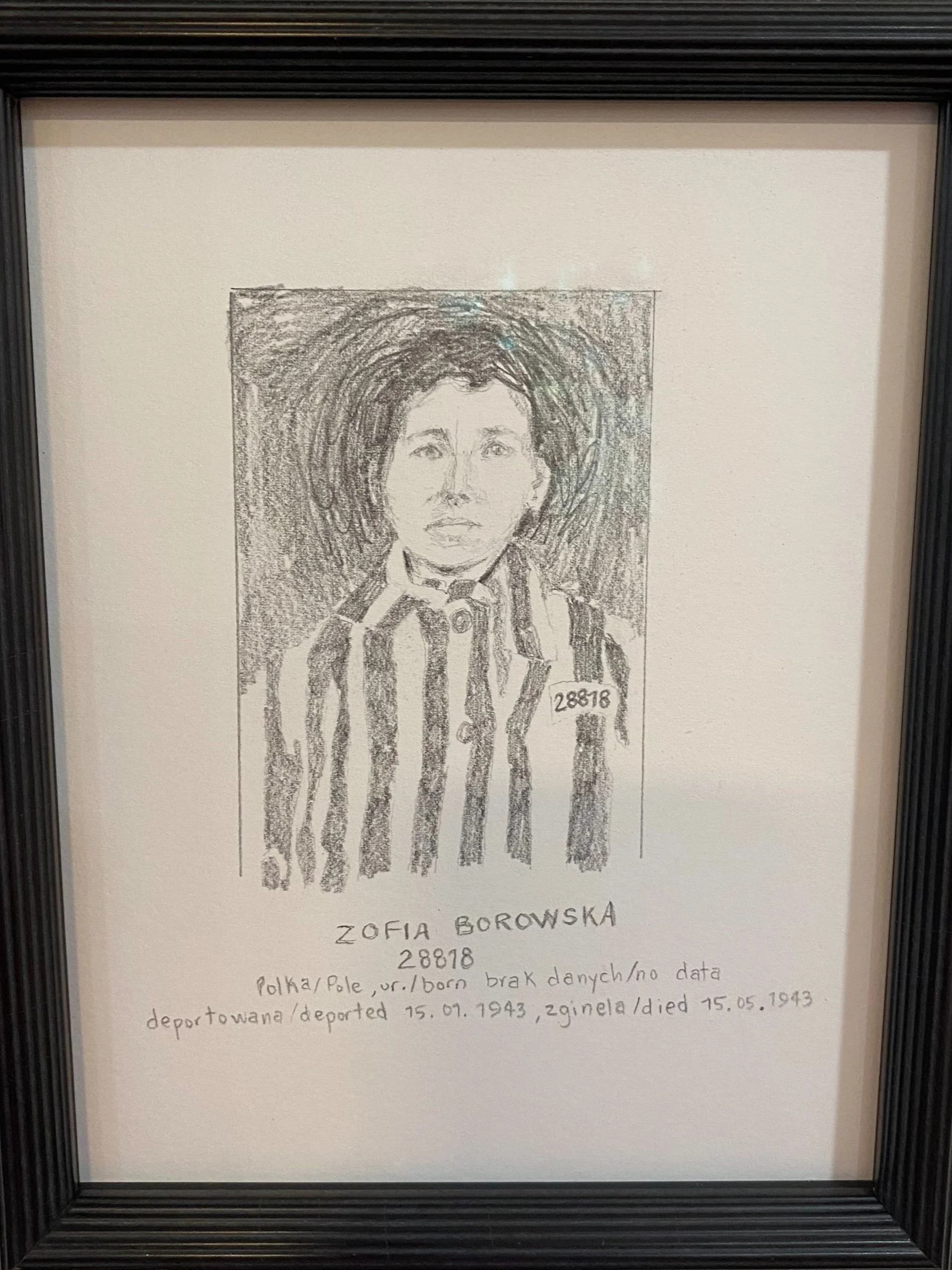

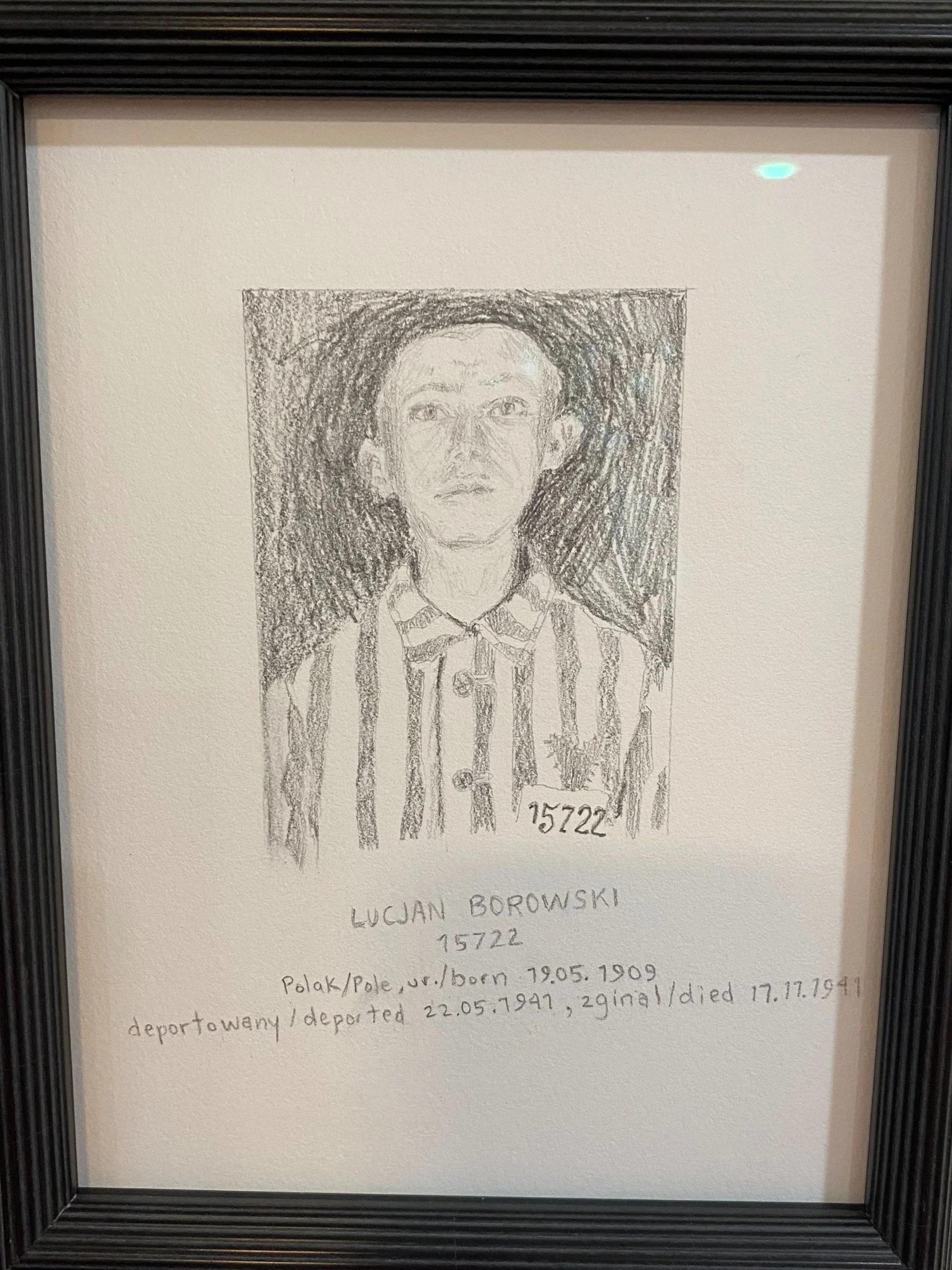

Auschwitz 120 days, 10” x 8”, graphite on paper, January 2024

Auschwitz 179 days, 10” x 8”, graphite on paper, January 2024

Untitled (Matt’s Birthday), 9 11/16” x 12 11/16”, graphite, watercolor, and 24 k gold leaf on paper, December 2023

Untitled (Myla), 11 1/4” x 9 1/4”, graphite and watercolor on paper, January 2024

Untitled, 8” x 8”, pencil, watercolor, and 24 k gold leaf on paper, November 2023

Untitled (Matvey’s 21st Birthday), 12 3/4” x 10 1/4”, pencil, watercolor, and 24 k gold leaf on paper, December 2023

Untitled (Myla and Piper Meeting Moose), 13 3/16” x 10 3/16”, pencil, watercolor, and 24 k gold leaf on paper, November 2023

Martin, 48” x 30”, oil on canvas, October 2023

One afternoon, November 27th of last year, my brother, Marty texted me asking me to go find my father, who had been driving around since eight o’clock that morning. It was 2:30 p.m. He was concerned because my father had been getting lost of late due to what we believed to be the beginning effects of dementia. Six months earlier, my husband thought it would be a good idea to place an Apple tag on my dad’s key ring and one in his vehicle after my dad reported to me that, sometimes, when he was driving around, he could not recognize where he was. Routine areas were becoming unfamiliar. I checked my dad’s location on the Apple tag locator on my phone. He was on Niagara Street north of downtown. He knew that area and I was certain he could find his way home. I did nothing. Mostly because I had attempted to drive to find my father on previous occasions but could never arrive at his destination while he was still there. Also, I hated him. I hated who he was-the offensive posturing, thinking that he’d better get the better of the world before it got the better of him-even to the point of criminality. I wanted to be nothing like him. So, I decided to sanitize him from my past-no more abandonment or other darknesses, albeit during his period of dementia, no more of his psychology sickening and corrupting me.

The upset, now deep inside me, bubbles up and replays over and over again in my mind, disturbing my thoughts and redirecting my consciousness toward terror. I wince. I grimace, my face unable to contain the horror. It’s like being gripped tighter and tighter by a giant invisible hand unable to move of one’s own volition or to breathe. How to drown out the voices? I analyze, classify, restructure, formalize, pathologize, and reframe my existence. Intellectualism is how I tamp down the cysts of truth and separate the little me inside, keeping little me covered and cloaked.

I remember when I was five. It was 9:00 p.m. and all of us seven kids were slung ‘round a banquette in a dirty bar. My dad brought us there in a drunken stupor to buy us all fish frys. I refused to eat the plate of getting-cold fish in front of me. Well…my father hit my mother. And although I can’t recall any times where this happened, my mother later told me in my teenage years that he used to hit her until she told him that the next time he hit her, she was going to call the cops. I just stared at him. Back then, I used to refuse to eat-when there were onions in the food or if it was something I didn’t like, or, and especially, if it were served in a disgusting bar late at night by someone who treated me disdainfully on the regular. He stared at me. I would not eat. But then my mother asked me. I cried as I ate, feeling a huge lump in my throat from the upset. Even at the tender age of five, I told myself I would never eat that fish again.

My brother texted me a few more times over the next few hours. I did nothing. Then, he called, pleading with me to go find him, “Please.” It was five o’clock. So, my husband, Denis, my two chihuahuas, Salty and Chauncey, and I climbed into our car and headed for the location of the Apple Tag-Niagara Falls, about thirty minutes from where we lived. Denis sped through downtown and along the Niagara river. We thought we had him, but by the time we arrived in Niagara Falls, the Apple tracker put him in Youngstown, the northernmost point in Niagara County about 30 more minutes away: go any further and you’re in Lake Erie. “We’re not going to Youngstown. Let’s just call the police and let them handle this. It doesn’t make sense. By the time we get there, he’ll be gone.” But Denis insisted. We started driving again. Except this time, the tracker stopped moving. Denis located it at a gas station on the lake. I called the police explaining that my father had dementia and was driving around lost. I shared his location then hung up. Denis found out the name and phone number for the gas station/pizzeria on his Tesla computer screen and called right from the car. He explained the situation and asked the attendant to look for a red blazer and a confused old man in his eighties. The attendant found the truck. It was empty. Denis thanked him, hung up, and continued. The police called back. The gas station attendant found my father and called an ambulance. That’s all we knew. My heart raced. We arrived on the scene a few minutes later. There was already a state trooper on the scene. We got out of the car and looked inside the vehicle, empty. Denis went into the gas station and inquired. We were led outside around the back of the building, down twelve steps and off a three foot concrete slab. At the bottom there was a fence, a bloody rag, and my dad. He had gone around the side of the building, presumably to take a pee, and had fallen down the twelve steps, off the concrete slab and onto a cinder block. He was in excruciating pain. His head was gashed in and bleeding. While we awaited the ambulance, my dad kept saying how mad he was at me for being in the predicament he was in. It was dark and starting to drizzle. It was freezing outside and he was not wearing his coat. By this time, it was 6:30 p.m.

The ambulance took my dad and me to St. Mary’s hospital in Lewiston. In the emergency room, I had a chance to talk to my dad and asked him some questions. He was so confused, really disoriented. The doctor said he was low on saline and fluids. An attending nurse gave him an IV of fluids, took some x-rays, and administered other tests. From his fall down that flight of stairs, he suffered a fractured pelvis and skull. Five hours later, they released him. We headed for Denis’ parents to borrow a toilet chair and a walker as walking for him was excruciating. The doctor also prescribed pain killers. On the way home from Clarence, we stopped by Mighty Taco and bought two tacos for him since he hadn’t eaten since that morning. He hates tacos. He complained. I read in The Encyclopedia of Mental Health, Volume 4, that old people, because of feeling unloved and unwanted, will retaliate with aggression and hostility by complaining about the food that they’re given. It was almost midnight and it was the only open restaurant. We arrived in North Collins around 1:30 a.m. and were greeted by my brother who we had been in contact with throughout the night. We settled my father in a recliner so he could try and get some sleep and left.

I arrived the next day to check on my dad and see if he and Marty needed anything. That’s how it went. I would show up at noon or just after and give Marty a chance to go to the store or wherever he needed to go for a couple of hours. He needed a break. Marty complained how tired he was, that my dad had not been sleeping and that first day, when Marty gave him the pain killers, my dad threw up and had diarrhea all over the bed. Marty cleaned it all up. “Marty”. “Marty”. “Marty”. My dad called my brother’s name every ten seconds. And he expected a response. That’s how it was-around the clock. So for more than two weeks, Marty didn’t sleep. He would cook for them. He would clean for them. After a few days, I realized that the situation was untenable for us. I sought help from an aide service. They couldn’t start the first week but were scheduled near the end of the second week. The first day they were scheduled to come, they canceled: the aide was ill.

On Thursday of that second week, my brother David and two of his helpers came over to my dad’s to empty and pick up my dad’s trailer. Marty suggested that we sell it to him. As they were emptying the trailer, Marty helped. I cooked supper for my dad and Marty that day, broiled fish and macaroni and cheese. I had somewhere to go that day so I only stayed for about an hour, cooked their meal, received $2,000 from my brother David to partially pay for the trailer, and headed for the bank. Everyone was still there when I left. There was a flurry of activity and a mess to clean up in the basement as the boys were just depositing my dad’s numerous tools from the trailer into the basement. It was probably one o’clock.

As usual, I arrived the next day but something was different. The screen door was locked. I wriggled my finger through the screen and unlocked the screen door. The kitchen door was locked too. No problem. I had a key. I opened the kitchen door and found my brother lying on the kitchen floor with his head resting against the cabinet. He was bloated and looked twice his normal size. And he was dark purple. Blood trickled from his nose and was forming bubbles with each of his breaths. My dad was sitting in a rocking chair beside him, just staring. I touched him. He was cold. The broiled fish was half-eaten and sitting in water in the kitchen sink. I asked my dad what happened and he explained that he had just fallen asleep there and didn’t wake up. My dad was too demented to know enough to call 911. So he just sat there and stared at Marty. I called 911. A State Trooper arrived maybe 10 minutes later. I explained what happened. He called the medical examiner who came a short while later. The medical examiner said that he suspected foul play and asked us to go into the living room. There was an indentation in the back of Marty’s head. In the living room, there were several nutty buddy wrappers and peanut crumbs strewn about the floor. Finally, a mortician came.

I don’t know what they did but all of a sudden, the house filled up with a horrific stench. I kept gagging, thinking I was going to vomit. I opened the windows for some relief even though it was winter. Then, from what I could hear, they put my brother inside a black bag and carried him off. I explained to my dad that he was going to come live with me now but he argued saying that he could live by himself in his house. The trooper had to insist that my dad come with me. He acquiesced. Several weeks later we received the results from the autopsy. Marty died from an overdose. There was crack cocaine, pain killers, and fentanyl in his system. He perished in the hours of the early afternoon which meant that my father sat in that chair watching Marty for next to 24 hours, subsisting on Nutty Buddies from the freezer until I arrived.

Marty used to hold our hands when we were little. He was just a bit older than my twin brother, Matthew and me. At eight, he used to build two story tree forts out of discarded old wood with jagged edges that he found in the woods. They rocked and swayed, being built into brush with branches that bent under our weight. But you could climb into them. And hide. At 18, he was a shoe salesman. Did he have a gift. He could talk to anyone, strike up a conversation about anything. The cart collector at Home Depot. The cashier at Tops. Near recently, he talked a state trooper into not carting him away during a welfare check. The trooper wouldn’t sit down and my brother turned the conversation around, after stating that he was neither a danger to himself nor others, by asking the state trooper why he wouldn’t sit at his kitchen table. Marty twisted the conversation suggesting that the state trooper thought he was better than my brother, and that was the reason he would not sit down. The trooper left after a few minutes, judging that my brother was, indeed, harmless. Unfortunately, at that time and for years before, Marty was experiencing paranoia. In his defense, his perspective was certainly twinged with truth. Members of the government who sometimes act in their own self interest became the C.I.A. is conspiring against me. The F.B.I. was wire-tapping his phone which was probably true because he was addicted to crack cocaine and was associated through his drug use with a most motley crew. Marty also believed that the current state of cities was an impossibility, that the buildings that we see are too numerous and old to have been built by human civilization.

Once, during the last two weeks of his life while he was caring for my father, he came downstairs in his boxer briefs, excusing himself, that he was so tired, he couldn’t even get dressed. I didn’t mind. But for all the men I’ve known, he was one who could be trusted with a woman. I knew he would never see me as a sexual object. I admired and respected that. It was unusual and welcome. The last few years, he was tormented. I saw him several times a week, and then everyday towards the end. I listened. I would suggest that what he was saying was true, at least to some extent, but what are we to do now, knowing that the government was trying to kill us (their policies, teaming up with big business and allowing the import and sale of items made of harmful toxins and poisons)? How are we to live our lives?

Fentanyl took my brother’s life. But what contributed to his being addicted to crack? I believe partly that he just had the right genetic makeup for addiction and that he lost the genetic lottery. But also it was his family of origin derangement, the poverty mindset, the lack of education, and most importantly, not having someone he could truly count on, someone who was even keeled and kind and compassionate, that kind of person in his corner. Although my father loved Marty, he cannibalized Marty’s life by always giving him a job, always giving him money all the while talking discouragingly to him, making him dependent so that my dad would not be alone. There comes a point when you must let go of your children. They must be allowed to pull up their own roots and transplant these into their own garden, digging their toes in new earth, where they can breathe fresh air and feel Spring rain and the winter frost. With each season they will lose last year’s leaves and sprout more and more plentiful new buds. In the warm summer months, honeybees will land on them and they then will bear seeds. The seeds will drop and begin to grow, growing leaves and stems and a strong trunk if allowed to flourish. But these new plants must also have room to grow to be healthy and strong and able to withstand storm. So, the second generation too, must let go.

Recently, I inquired at a Veteran’s old folks home about whether my dad could live there. In preparation, I pulled out an old hard cover text of the time when my dad was in the Air Force. He was stationed at Smoky Hill Air Force Base in Salina, Kansas in the 802nd Food Service Squadron in the fifties. He was an Airman Third Class and, looking at his picture, was not entirely thrilled to be there. He repeatedly told me that he joined the armed forces to eat. In the portrait, he looks so young and uncomfortable, really sad. He looks lost, too, as though in a blinding storm with no one coming to help. So, although I’ve already told you that I hated him, the prose that I’ve cobbled together here is not neatly assembled into one tightly bound garment, and is, in fact, threadbare. When I look at his picture, I feel sorrow and tenderness; there is a common thread that I share with my father, that being needing love and tenderness and affection, to be understood and welcomed, but not only not knowing how to obtain these, but that we rabidly work against and make enemies of those who would try to give us this.

Untitled, size TBD, small, pencil and watercolor on paper, September, 2023

Untitled, 14” x 11”, oil and 24k gold leaf on canvas, August 2023 Private Collection

Untitled, 20” x 16”, pencil and watercolor on paper, August 2023

Untitled (Jen), 20” x 16”,, pencil and watercolor on paper, 2023

Untitled (Stella, Jake, and Brian), dimensions TBD, pencil and watercolor on paper, 2023

Untitled (Denis in gold), dimensions TBD, pencil and 24k gold leaf on paper, 2023

Untitled (Franklin and his uncle), dimensions TBD, oil and 24 k gold leaf on canvas, 2023 Private Collection

Winter, dimensions TBD, pencil and watercolor on paper, 2023

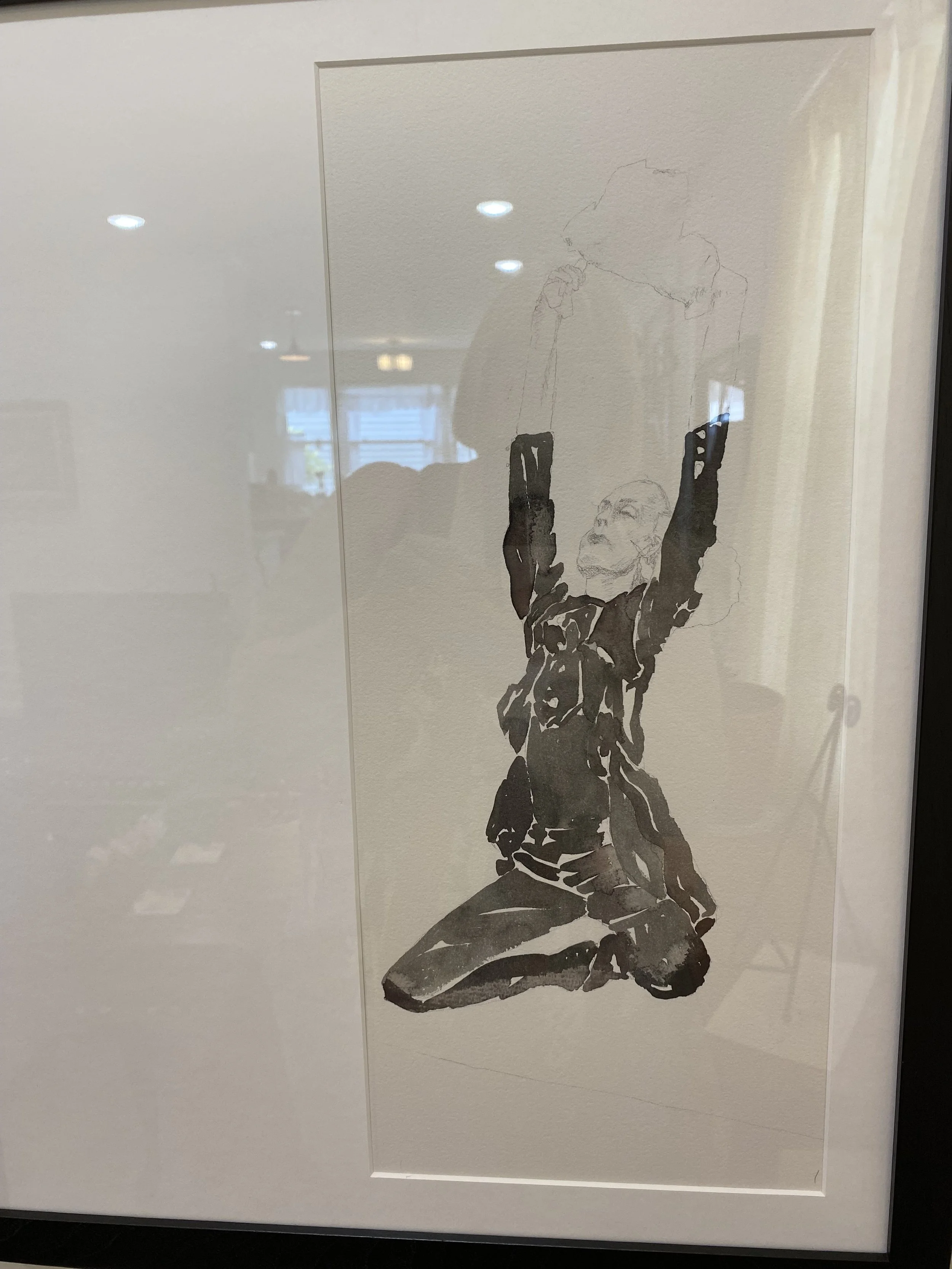

Hello Dolly Series #1, Dancer in Black Leaping 21.5” x 17.5”, pencil and watercolor on paper, 2023

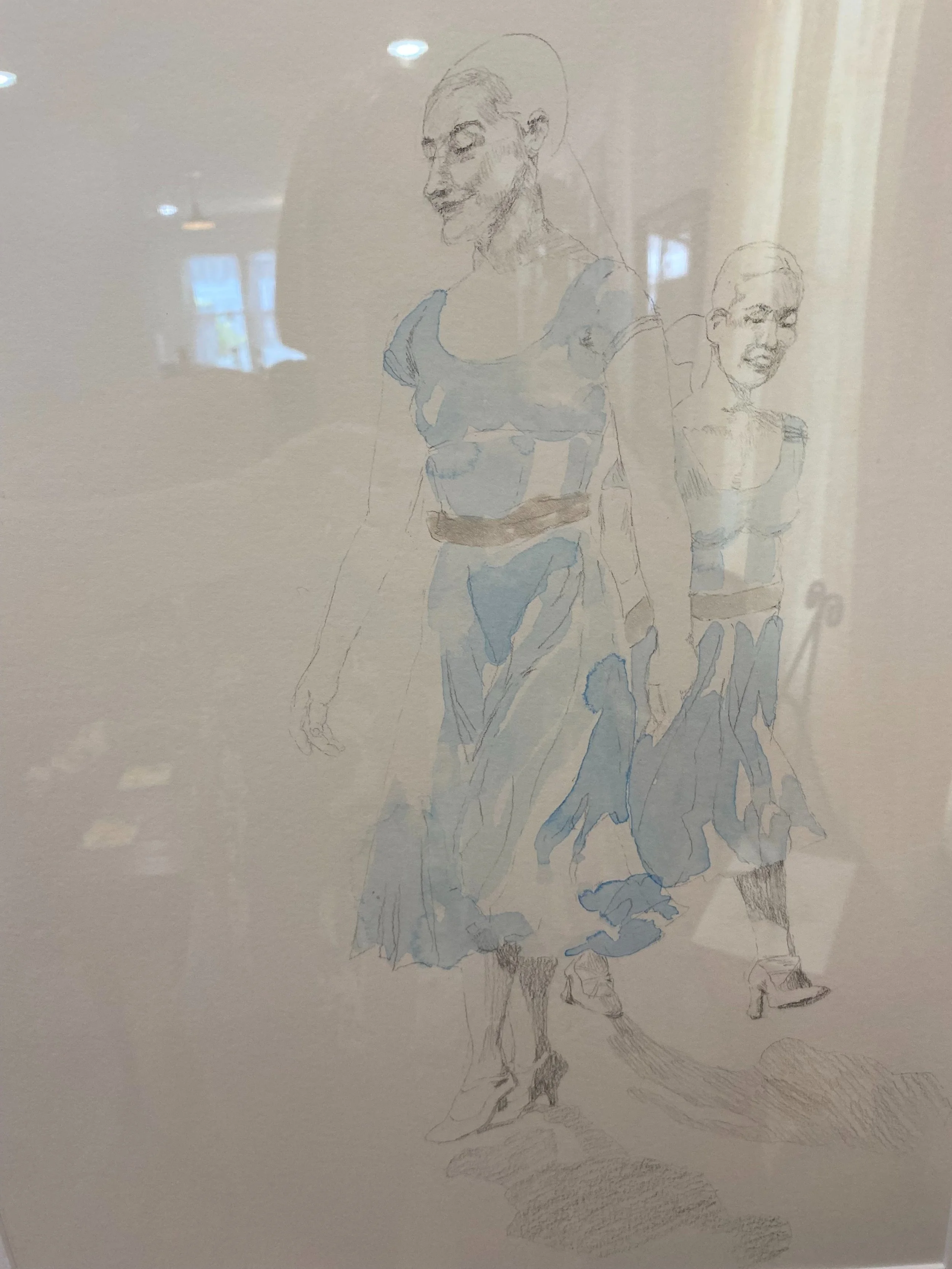

Hello Dolly Series #2 Dancers in Blue, 20.75” x 16.75”, pencil and watercolor on paper, 2023 Private Collection

Hello Dolly Series #3 The Voyeur, 22.5” x 18.5”, pencil and watercolor on paper, 2023

Mary in Egg, 21.25” x 17.25”, pencil, watercolor, and 24k gold leaf on paper, 2023

Jesus and Mary, 21.25” x 17.25”, pencil, watercolor, and 24k gold leaf on paper, 2023

Julie, 16” x 16”, pencil and watercolor on paper, 2023

Tree of Life, 28.5” x 35.75”, pencil, watercolor, and 24k gold leaf on paper, 2023

Mom, 21” x 17”, pencil and watercolor on paper, 2023

Kailynn, 22.5” x 18.5”, pencil and watercolor on paper, 2023

Piper, 21” x 17”, pencil and watercolor on paper, 2023

Untitled, dimensions TBD, pencil, watercolor, and 24k gold leaf on paper, 2023

Piper and Myla, 22.5” x 18.5”, pencil and watercolor on paper, 2023

Julie, David, and Me, small, dimensions TBD, pencil and watercolor on paper, 2023

Untitled, small, dimensions TBD, pencil and watercolor on paper, 2023

Untitled, 22’ x 28’, pencil and oil on canvas, 2022

Untitled, 11’ x 11’, pencil and oil on canvas, 2023

Jesus Christ

The Lord’s only son

Made no provisions

His shackles were none.

Untitled, pencil on paper, 2022, Private Collection

Untitled (Tom’s gift), pencil and watercolor on paper, 2022, Private Collection

Untitled, 48” x 30”, oil on canvas

I dreamed of Queen Elizabeth II in the winter of the northern hemisphere, two thousand twenty-two. There was a vibrant orange and yellow and gold wheat field. The sky midnight black. In the field there was a black sedan. In the back seat behind the driver’s seat there was a woman. Then she was gone. At the moment she perished-I won’t say from the earth as that is uncertain-the Queen appeared as a figure-eighty feet tall. She materialized as thousands of brilliantly-colored, glowing embers, each in color and luminosity as a jewel. I am unable to interpret the dream as God has not given me the discernment to interpret this vision.

Untitled (1966 Chevelle Super Sport), 22” x 30”, pencil, ink, and watercolor on paper, 2022

twins, 15” x 12” & 14” x 11”, oil on canvas, 2022

Matthew was born with black eyes, as if their physical presence inlet the cosmos. There was no detectable sclera. We called him rat, derision a family tradition. It all began with him. His realm was not of this world and he commanded no army. Matthew was my twin. He had a dolly with coke bottle glasses and hard plastic eyes that didn’t close. He taped gauze over its eyes like the ones he had to wear. Amblyopia, they said. Doctors “fixed” it by making him color in o’s in Reader’s Digest magazines for so long that I can remember him screaming. We were three years old. I glared at the doctors as we left.

We lived in a place called Shantytown. There was no sign, not even a road really, just dirt peppered with a few stones. The “road” was bedecked with seven ramshackle houses. There was Mrs. Rupert who we stole pears from, Lu Ann and Barbie’s, my aunt and molesting uncle’s, R.J.’s family, the crazy guy who circled our house with a shotgun once, the people who never came out, and us. There was an air to it, like living there required more than just the resignation of one’s dignity. It just wasn’t pretty except to us. The land extended beyond the last house for several acres. There was neglected brush and weed and a few trees, mostly just tall grass in an opening. Everything was brown from June to September. Whatever growing season meant elsewhere never drifted as far as Shantytown.

To me he was always Mitchy the Match, five year old arsonist. When we were five, we found some matches. Actually, we looked for them, knew where to look, and stole them. We lit some brush on fire just to see what would happen. I guess you don’t really know what a wildfire is until you’re standing in front of it. There is no “front of it.” I can’t remember how we got out of there. But I do remember firemen threatening to take us to the police precinct. I pretended to be scared. We didn’t discontinue arson services, we just sought the certain expertise of an older gentleman, R.J. He was eight. Once, R.J.’s father caught us. He lit one burner on the stove. After several minutes, he branded R.J.’s arm into the wrought iron. He held it there while we watched. Certain screams you know. Then you come across one you don’t. That’s how R.J. screamed. It was a pitch that didn’t belong to an eight year old boy. It wasn’t his scream that was so unnerving. It was hard knowing him after that.

Matthew first began using drugs by inhaling my dad’s construction chemicals. He was eleven. I don’t know how much later, and then for the rest of his life, he was addicted to heroin. There was an open sore on the tender side of his arm in the place where blood is drawn, a couple inches in diameter. It was black, a black I’d never seen, the color of no living thing. The skin changed to something else, something that could withstand the abuse. Its outer edge quit trying to heal years ago. It could no longer be tender. Moving toward the center the tissue became less stable, like any internal structure ceased and resigned itself to nothingness. Polyps surrounded the inner hollow. The innermost ring was pulp, cleaving away what had been left of what once was skin. There was no mucus, just an opening in the center. I looked quickly. When I looked at him he was four again with patched eyes and crooked teeth. I think at four he was already lost, that what had been done to him was already done and he would just have to await death like the rest of us. I didn’t want to look again. I couldn’t bear knowing him like that. And that is how I let him go. I withheld my only possession, me. I didn’t want him to see that the world in its state had already removed me from my person. Missing teeth were only souvenirs of my time here. My beauty, like his, remained hidden from those who’d excavated hope, paving over its ruins without sentiment.

For years beyond remembrance, I hid what it meant to see his body rot from an existence unimaginable to me. I tried. Abuse can be as commonplace as substance and infinitely bearable. What is intolerable is witnessing your own heart captive in another. Existence only lets the most tender piece of it exist within another. It’s too true to bear alone. It is held without consideration or ransom. The heart is not one thing that exists within any of us. It’s really a conglomerate. It exists within all of us, every living, sentient being, its true mechanism unknown. It reveals itself only in the presence of god. This presence only mirrors. It allows the grief-stricken its loneliest day, the lost displacement, the damned self hatred. That was him. He walked with the air that today, that everyday just might be his last.

Matthew never looked at me. It was what he could do. He was the least of all branches, cleaved down before compassion took dominion. He was defenseless. By twenty, his honeycomb nature had collapsed.

Peter, 30” x 24”, oil on canvas, c. 2020

Marjorie Kitchen

Buffalo, New York

December 14, 2021

Peter Gutowski

Oakland, California

Dear Peter,

I wanted to write to you to share some of my cherished memories of you, in childhood. One of my favorites was when you were about four. It was in my backyard. There was a small pond right outside the backdoor off the kitchen, maybe three feet long and a foot and a half wide. It was shallow as well, perhaps only ten inches deep. It occurred after a summer rain and you could smell all of the unearthed worms splayed on the concrete driveway. We spent the morning in the sun “sailing” leaves in the pond. We watched how they floated. Well that transformed into a game where we would gently place found items from the backyard onto the pond surface and see if they would sink or float. We guessed before each voyage. I still remember the sun gleaming off your almost-white blond hair.

A second favorite memory I have of you is when you were between two and three and still drinking from a baba. I would fill your bottle up with grape juice and set you down for a “nap” on a colorful crocheted afghan in front of the television to watch “Little Bear.” It was your favorite show. Well, you never actually went to sleep but would teeter and rock back and forth from side to side while on your back watching Little Bear and his friends have their adventure. I don’t think you ever really took a nap. You had boundless energy.

I remember a third memory. You were in preschool, maybe three years old. It was a beautiful summer day. The sun was shining. The air was warm. The nursery school you attended was having a backyard carnival with water tables, bubble stations, and balls for bouncing. Do you remember Ms. Deena? She was your teacher. She was beautiful, caramel brown, and had short, wavy hair and bright eyes. She was very kind to you. We stood and knelt, respectively, around a small water table filled with toys. There were two or three other children standing around the table, hesitant to start playing. You took a bucket, filled it with water and then dumped it out. Over and over. You looked up at the other kids and said, “Hello.” They smiled, then joined in the fun. You were always doing that, saying hello first and inviting others in.

But my favorite memory was when you were four. One day, I gave you a roll of scotch tape and you taped every piece of furniture in my living room together(it was a rental). You were busy for about an hour, busy capturing a table leg, then a chair arm with the sticky surface of the tape. You never snipped off a piece, but extended the entire length of tape over my unassuming house. It was like a huge spider web-well, a spider on caffeine. We left it up all day and showed your mom, who wasn’t sure at all if that was a good idea. But what fun!

Merry Christmas,

P.S. May this letter bring you comfort if the day comes that the wind howls at your door.

Untitled, 30” x 24”, oil on canvas, c. 2020

I imagine the heart is like a reverse bruise. It starts red. It has only one purpose. It’s not even aware of it. After one or two days, it becomes bluish with no inlet. Now color denotes tenderness. It is purple too. It is tender. It winces when touched. Color augments until perception is deep within the tissue. There are splotches where part of it heals faster than another. The skin offers itself to increased scrutiny. A slight yellowing begins. There is no edge, only where it is jaundiced and where it is not.

The Man in Black, 11” x 11”, oil and 24 karat gold leaf on canvas, 2022